Powerful evidence based on the personal experience of a former heroin addict who became a brain scientist

I spent most of my life mindlessly obsessing about the past and the future. I was consumed by anxiety and tormented by my mind, but completely unaware of the source of my suffering.

To escape my pain, I used drugs, resulting in 15 years of chronic heroin addiction. Heroin brought me to the very edge, but I was lucky. Pounded into submission by the most painful night of my life, I was forced to look at the world from a completely new perspective.

That was in October 2013, when I was first introduced to mindfulness. Since then, I’ve become an author, a Ph.D. student, and a lecturer at the top two universities in Ireland, all in the area of the neuroscience of mindfulness.

Understanding the science underlying mindfulness and meditation can be a powerful motivation for anyone building these habits. But it’s especially helpful if you’re the kind of person who wants evidence of efficacy before embarking on a new goal. (Gretchin Rubin characterizes this as a personality type of “questioner”.)

How the Brain Works

Neurons

Neurons are the basic building blocks of your brain, and there are about 86 billion of them. A single neuron fires between five and fifty times per second, and on average, each neuron receives five thousand connections from other neurons. So, in the time it takes you to read this sentence, billions of neurons will have fired inside your head — a complex system, to put it mildly.

For every action, thought, and feeling you will ever have, it’s neurons firing that allow you to make sense of the experience. This is the biological basis of learning. The more you practice a certain behaviour — say, mindfulness, or worry — associated neurons become more practised.

These neurons are then required to fire more often and more quickly. To save energy, the brain creates new structures specific to the job at hand. This is the essence of learning, and what we call neuroplasticity.

Neuroplasticity

Our brains are malleable, like playdough, and our experiences determine their shape. This process is best compared to physical exercise. For example, thirty reps in a gym won’t make your muscles bigger, but thirty reps every day for a year will. The same is true for your brain, and over time, its shape will change.

As a perennial worrier, I always felt tense, uneasy, and anxious. If my mind wasn’t scanning the world for potential threats, it was looking for ways to relieve my unrelenting anxiety. Over time, I literally transformed my brain into a finely tuned anxiety machine.

It’s the same for any negative feelings, thoughts, and emotions. Whatever you rest your mind upon, be it anger, self-doubt, or fear, your brain will eventually take that shape.

The reptilian brain

The human brain can be loosely divided into three regions: the reptilian brain, the limbic brain, and the cortex.

The reptilian brain, the oldest of the three brain regions from an evolutionary perspective, is responsible for the body’s vital functions, such as body temperature, heart rate, and breathing. This structure is also in control of our instinctual and self-preserving behaviours, which ensure the survival of the species.

This primitive part of the brain, which is also responsible for reckless and impulsive behaviour, can be highly problematic. Its need to survive is so powerful that it often fights with the logical part of the brain, the cortex.

It’s like two different people having an argument. “Go on, have a drink.” “No, I better not.” “Ah, sure I deserve it.” “Yeah, but you’ll regret it later.” If you’re an anxious person, as I was, the reptile brain sees feelings of anxiety as a threat, even when it doesn’t know what’s causing them.

Through experience, it knows that a drink can relieve anxiety, if only for a short while. So when you say yes to that drink, the reptilian brain has won. I often think back on my drug-induced years when my impulsive behaviour was controlled by my reptilian brain. There was never a fight, just a winner — the crocodile always got his drugs.

The limbic brain

The limbic brain is comprised of several structures, found above the reptilian brain. The main components include the hippocampus, the amygdala, and the hypothalamus.

The limbic brain supports a variety of functions. The hippocampus is essential for memory formation. The amygdala, located next to the hippocampus, plays a key role in emotions like fear, anxiety, and anger. The amygdala is also responsible for determining the strength of stored memories, whereby memories with strong emotional content tend to stick.

The hypothalamus, which links the brain to the endocrine system, is a vital component of our stress response. It produces chemical messengers that can both stimulate or inhibit stress-releasing hormones.

The cortex

The cortex, the most recent addition of the three brain regions, consists of grey matter surrounding the deeper white matter of the cerebrum. Grey matter contains the bodies of neurons, and white matter consists of the connecting fibres between different grey matter cells.

The cortex is the part of the brain involved in higher-order functioning, such as abstract thought, problem-solving, appraisal of danger, and language. With unparalleled learning capacities, this highly flexible structure has enabled humans to do things no other species has done.

The stress response

In times of stress, the three core structures of the limbic system — the hippocampus, the amygdala, and the hypothalamus — work together in tandem.

Consider this example. You are walking through a field when you see what looks like a snake. Stored memories in the hippocampus remind you that you’re scared of snakes. This lights up your amygdala — the fear centre of your brain — which activates your hypothalamus.

The hypothalamus then sends a signal to your pituitary glands, which in turn, sends a message to your adrenal glands releasing cortisol throughout your bloodstream. Cortisol is the primary stress hormone, which prepares your body for fight or flight.

The Neuroscience of Mindlessness

It’s not life or death

The cortex, the reptilian brain, and the limbic brain collectively work together. They are interconnected by complex neural pathways (white matter) that have developed to influence one another.

In the snake example above, a survival response from the reptilian brain would have activated the limbic system, releasing cortisol throughout your body. This speedy bodily response is what gets you out of immediate or potential danger.

At the same time, however, the rational part of the brain, the cortex, appraises the situation. This is a slower process, and if you’re lucky, you realize that the snake is actually a piece of rubber. When this happens, the cortex deactivates the amygdala, which in turn inhibits the secretion of cortisol via the hypothalamus, thus bringing the body back into homeostasis.

This is a very simple example, but in real life, things are never quite so black and white, especially in today’s busy world. When I think of how this relates to the old anxiety and addiction ravaged me, I get a headache. But let’s give it a go.

My anxiety, which resulted from childhood trauma, centred on bodily sensations. Ever since I can remember, I was terrified of my heartbeat, breath, and pulse. If someone asked me to feel my own heartbeat, or if I even talked about it, my amygdala lit up like a Christmas tree.

The reptilian brain, always thinking of self-preservation, said: “Right, I’ll get you out of this shit, pal.” So what did I do? Anything to get away from myself, anything to quieten my overactive mind — and for me, that was drugs.

I often wonder what my rational mind, the cortex, was doing during this time. My heartbeat wasn’t going to kill me. I was never in any real danger. Surely my logical mind knew this. Wasn’t it supposed to tell my limbic system that everything was OK?

Neuroscience provides us with many potential theories to explain these questions. The cortex might be worked too hard by an overactive limbic system, or simply unable to use logic to eliminate irrational fears. The truth is, we don’t know for sure, but understanding the basic mechanics of this system has provided me with a framework to realize that there is nothing to worry about — certainly not life or death stuff anyway.

Emotional hijacking

Have you ever felt completely shaken and overcome by fear? I have. I was easily overwhelmed before and during my addiction — it was my default. Daniel Goleman calls this an emotional hijacking, where your amygdala screams like a siren.

This happens when something in your environment triggers a stress response. It might be your partner raising their voice, a work colleague criticizing you, a close call on the road, or someone giving you a fright.

From a neuroscience perspective, the visual or auditory cortex — depending on whether it was a visual or verbal stimulus — sends a message to your amygdala, and a stress response is activated.

You would think this is how most people experience stress, and it was certainly how it evolved in our species. But in today’s busy world, more often than not, the stress response is not activated by the external environment — it is activated by our own minds.

This comes in two flavours: ruminating about a past you cannot change, and worrying about an imaginary future. These internal stressors are the worst kind of triggers. External stressors come and go, but fighting with your own mind is constant. And when it comes to stress, it’s like forgetting to tighten the cortisol tap when you leave the bathroom…drip, drip, drip.

Neuroscience of Mindfulness

If you’re persistently anxious, angry, or self-loathing, your brain will eventually take that shape. At the same time, however, you can shape your brain in a much more positive direction.

By harnessing the power of neuroplasticity via regular mindfulness practice, you can become more resilient, develop sharper focus, and manage your emotions more effectively.

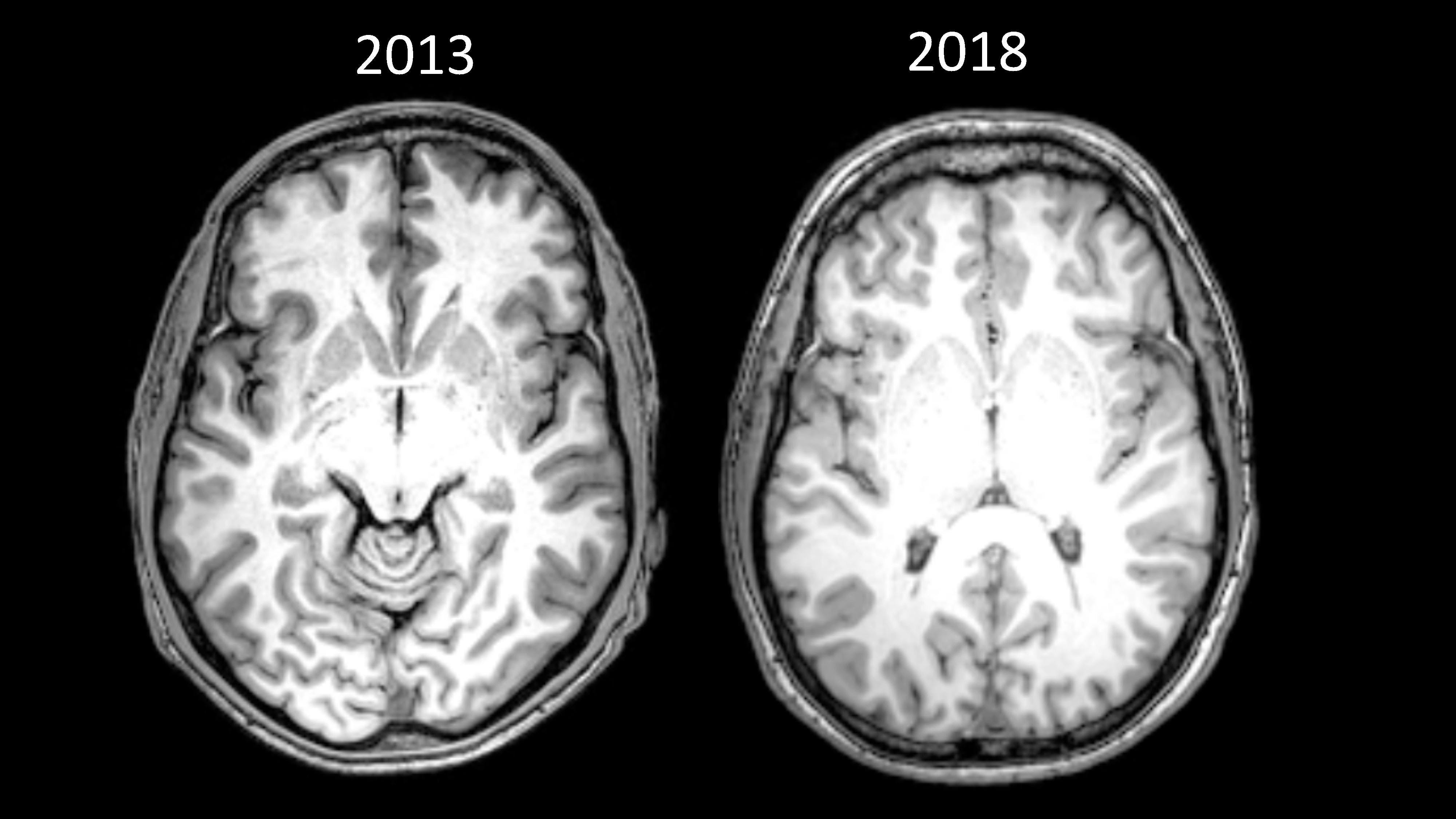

The images below are scans of my own brain. The one on the left was conducted as part of a study in 2013 — when I was only two days clean, after 15 years of addiction. The one on the right was taken in May 2018 as part of a TV documentary about stress.

My brain was so different that the person analysing the scans could not compare the standard visual markers by eye (see the note above for a more technical explanation).

It is difficult to specifically account for what caused these changes. In the four and a half years between the scans, I radically overhauled many aspects of my life, including diet, exercise, and sleep. I also went back to college and, of course, I stopped taking heroin.

But for me, present moment awareness provided the foundations for all of these changes. From the day I was introduced to mindfulness, everything changed. It gave me a tool to cope with my greatest adversary, anxiety, and everything just flowed from there.

Emotional regulation

Research shows that a regular mindfulness practice significantly weakens the amygdala’s ability to hijack your emotions. This happens in two ways. First, the amygdala decreases in physical size. Second, connections between the amygdala and the parts of the cortex associated with fear are weakened, while connections associated with higher-order brain functions (i.e. self-awareness) are strengthened.

My own mindfulness practice has given me both of these gifts. I have literally shrunk the fear centre of my brain, and as a result, I simply don’t feel fear and anxiety like I used to. Stressful events still challenge me, but by creating a space between stimulus and response, I am no longer hijacked by my emotions.

Attention and focus

The area of the brain associated with attention is a structure called the anterior cingulate cortex. It has also been linked to self-regulation and flexible thinking — the opposite of compulsive and rigid thinking.

Research has found increased volume in this area of the brain after mindfulness practice. What’s more, when the connections between the amygdala and the rest of the cortex get weaker (i.e. the areas associated emotional hi-jacking), attentional control becomes stronger.

One study showed that practising mindfulness for only 20 minutes per day for five days can lead to improvements in attention, while a more recent study showed that a brief mindfulness intervention improves attention in complete novices.

Self-awareness

“Self” means your self-concept, your story — who you think you are. If you are suffering in some way, like I was with anxiety, disconnecting from “self” will give you the freedom to experience a greater sense of wellbeing.

Through improved self-awareness, mindfulness can provide a detachment from the self. Instead of being controlled by your self-concept, an ability to observe or experience the old you will emerge.

Although research in this area is only just emerging, some promising studies have targeted an area known as the default mode network (DMN), also known as the wandering “Monkey Mind”.

The DMN is active when our minds are directionless, aimlessly drifting from thought to thought. This has been linked to rumination and overthinking, which can be extremely counterproductive to our personal wellbeing.

Mindfulness has been found to decrease activation of the DMN, and in effect, to quieten our busy minds. In one study, regions of the DMN showed reduced activation in meditators compared to non-meditators, which has been interpreted as a diminished reference to self.